The state of pandemic education, two years on

While gaps remain in learning despite the return to the physical classroom, cooperation from all quarters could be enough to bridge the gulfs and help students make up for the time lost to Covid-19.

Just In

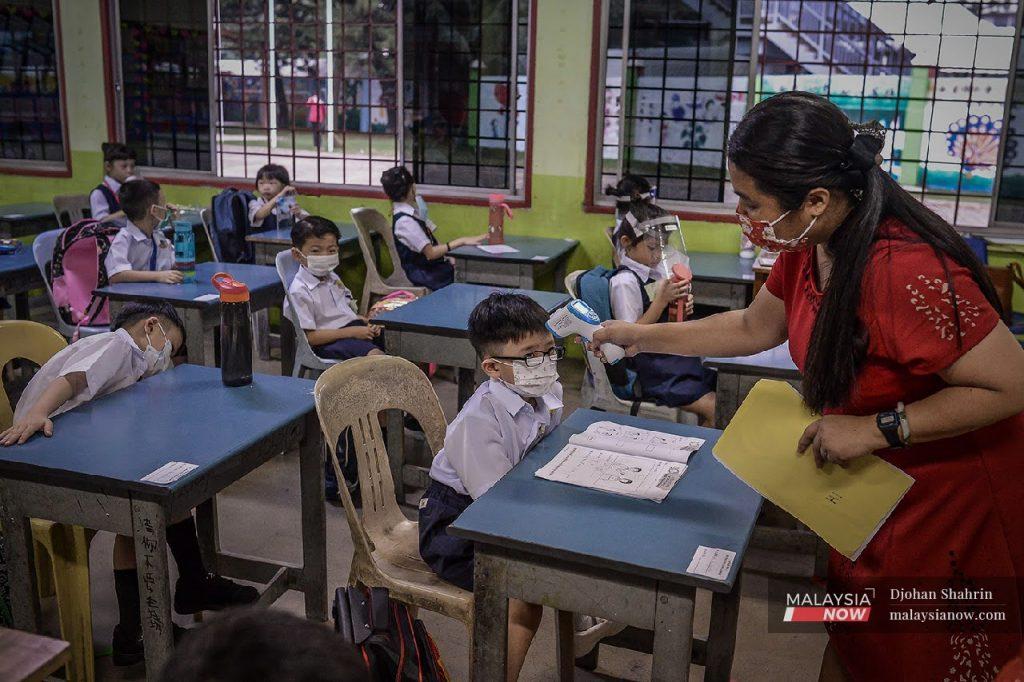

While Malaysia’s pandemic situation appears to be stabilising from some aspects, concern remains over educational development even as students begin returning to school for face-to-face sessions after more than two years of classroom disruptions compounded by the recent floods disaster.

This week saw tens of thousands of students across the country flock back to physical classrooms following a long break prolonged by the massive floods which pushed the starting date of face-to-face lessons back by a week.

But it will be some time yet before the gap caused by the Covid-19 pandemic can be plugged, according to the Malaysian School Principals Council.

Council president Mohd Ariffin Abdul Rahman said the pandemic had had a significant impact on students’ learning process.

Speaking to MalaysiaNow, he estimated that students have been left an average of three months behind in their lessons.

“If we use face-to-face teaching and learning methods without rotation, the learning syllabus in school can be completed in about six months’ time, especially for Standard One students,” he said.

“However, the time required to master the syllabus may take longer if we use the home-based teaching and learning method (PdPR).”

PdPR was by and large the only form of learning possible for students throughout the pandemic period, especially when large-scale lockdowns or movement control orders caused the closure of the social and economic sectors.

But the recent months have seen Malaysia gradually reopening, with interstate travel restrictions lifted late last year on the back of a strong vaccination programme which has seen nearly 98% of adults fully jabbed so far.

During the early stages of the pandemic, Ariffin said, the hope was that it would pass quickly. At this point, he added, the focus was on public health and not so much on education.

But once the pandemic began stretching past months and into years, several alternatives were developed to ensure that students could continue learning despite the health restrictions.

For example, some schools ran flexible PdPR lessons that continued until evening or night, allowing students to contact their teachers at any time with questions about their lessons.

But Ariffin said the freedom gained by students through their use of multiple devices and borderless access to applications had seen some of them diverted to activities that were not beneficial to their education.

He gave the example of students who play games throughout the night, disrupting their sleeping patterns and causing them to oversleep. Such students often ended up missing their PdPR classes, widening the learning deficit which would then take longer to resolve, he said.

Ideally, he said, if every student consistently followed their lessons through PdPR, the syllabus could be finished on time.

Yet this was rarely the case, owing to factors such as students’ attitudes, parental management of learning at home, different home environments, and internet access, among others, he said.

Ashvini Murugan, whose two sons are in Form One and Standard Two, said the pandemic had changed the way she envisioned the future for her children.

She agreed that some children had lagged behind in their lessons when schools were shut but said that they had struggles of their own.

“As a parent, I am worried about their academic performance during the pandemic but as much as it isn’t easy for us, it isn’t easy for them, either,” she said.

While she still believes strongly in the importance of formal education, she said students appeared to have developed their own skills in specific areas of interest.

“They are very fast to learn when it comes to digital technology,” she added. “I think that is their advantage.”

And despite her concerns, she also believes that huge possibilities await.

“For now, we just need to make sure they get the best education they can.”

Ariffin meanwhile said that demand for spots at boarding schools and universities had remained strong throughout the pandemic period.

“School and university education is still the most important space to improve the socioeconomic status of those in the younger generation,” he said.

“They will have a bright future if everyone moves together to address the issues that need to be addressed, and solve them together.”

And as much as PdPR had helped keep education alive throughout the pandemic, he said, face-to-face classes remained crucial.

“If everyone works together to propel the children towards education, the country’s progress will not remain hampered for long.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.