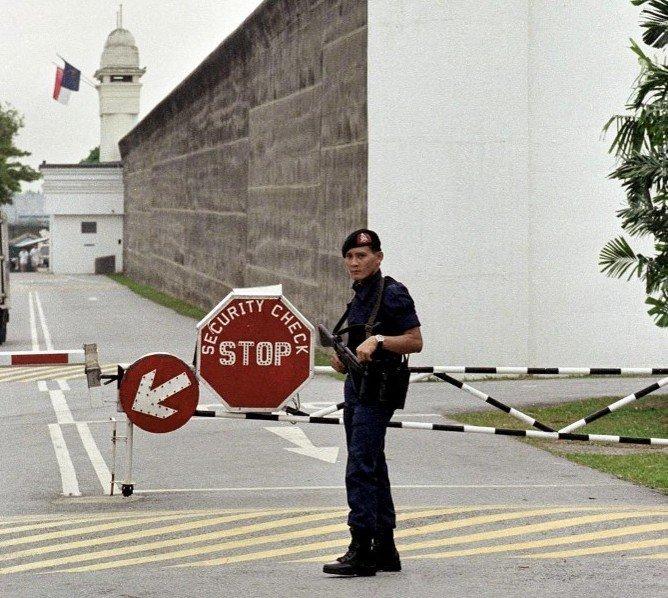

‘Like sardines in a can’: Ex-inmates detail ‘dehumanising’ experiences in Singapore jails

A report by the Transformative Justice Collective says a lack of oversight has led to abuse, mental health issues and the denial of basic rights.

Just In

A report by a rights group appears to have shed some light on the circumstances in prisons throughout the city-state, which has been under international scrutiny lately over its use of the death penalty for drug mules, most recently Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam who was executed despite an outcry over his limited mental capabilities.

The Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), in its report titled “‘You Don’t See the Sky’: Life Behind Bars in Singapore”, interviewed 36 former inmates: 27 males, eight females and one transgender female.

The majority of its respondents were of Malay or Indian ethnic origin. More than half had been to a drug rehabilitation centre in the island republic, with a “significant number” having served prison sentences for drug-related offences.

Respondents were questioned about the prison conditions, how they were treated within the prison system, and how they felt about both.

The report described Singapore’s prison system as “extremely regimented”, with inadequate and dehumanising cell conditions.

One of the prisoners said they had been kept “like sardines in a can” with up to four inmates placed in cells measuring approximately 2.5m X 2.5m, including the space needed for a toilet.

“They (prisoners) sleep on hard cement floors and are only issued straw mats to lie on. There was barely enough space between one person and the next when everyone lay down to sleep,” the report said.

This was far below the guidelines by the British organisation National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders, as well as the Mandela Rules which specify the standards in cell size, occupancy, bedding, lighting and ventilation.

The TJC report also claimed that Singapore prisons practise what it described as “extrajudicial punishment” like caning, solitary confinement, and denial of yard time.

“Prisoners were not allowed to exercise in the cells, and activities such as counselling, family visits, work programmes and recreation are not guaranteed rights,” it added.

According to the report, facilities such as ventilation and fans are not provided. Respondents in the interview also told TJC that the lack of room, absence of mental stimulation and interrupted sleep made them feel like they were “going crazy”.

A former convict also spoke of a deterioration in mental health which he blamed on the cell conditions.

“Sometimes what you need is a private space to cry, to let out your emotions. It’s impossible inside there,” he said.

Another respondent said frustration and restlessness over the confined space led to prison fights among inmates.

The report also cited instances in which inmates’ privileged correspondence including their communication with their lawyers was forwarded to the Attorney-General’s Chambers.

TJC said Singapore’s incarceration system had failed to meet its objectives of rehabilitation and care, and criticised its campaign to give more opportunities to former convicts.

“The state narrative surrounding incarcerated persons, including the Yellow Ribbon Project – which only showcases success stories of rehabilitated individuals – excludes the experiences of those who have been traumatised and abused by a system which shows scant respect for their dignity and rights,” it said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.