Malay duo fight to stay alive on Singapore’s minority-ridden death row

Some 90% of death row inmates are ethnic minorities, despite Singapore's clinical approach to creating racial balance.

Just In

Singapore’s long-defended approach to engineering a sense of equilibrium in its multiracial population appears to have missed out the justice system, as statistics indicate that the country’s minorities are by and large at the receiving end of tough sentences.

Some 90% of those currently on death row in the republic’s prison are ethnic Malays and Indians, whose communities comprise just over 20% of the population.

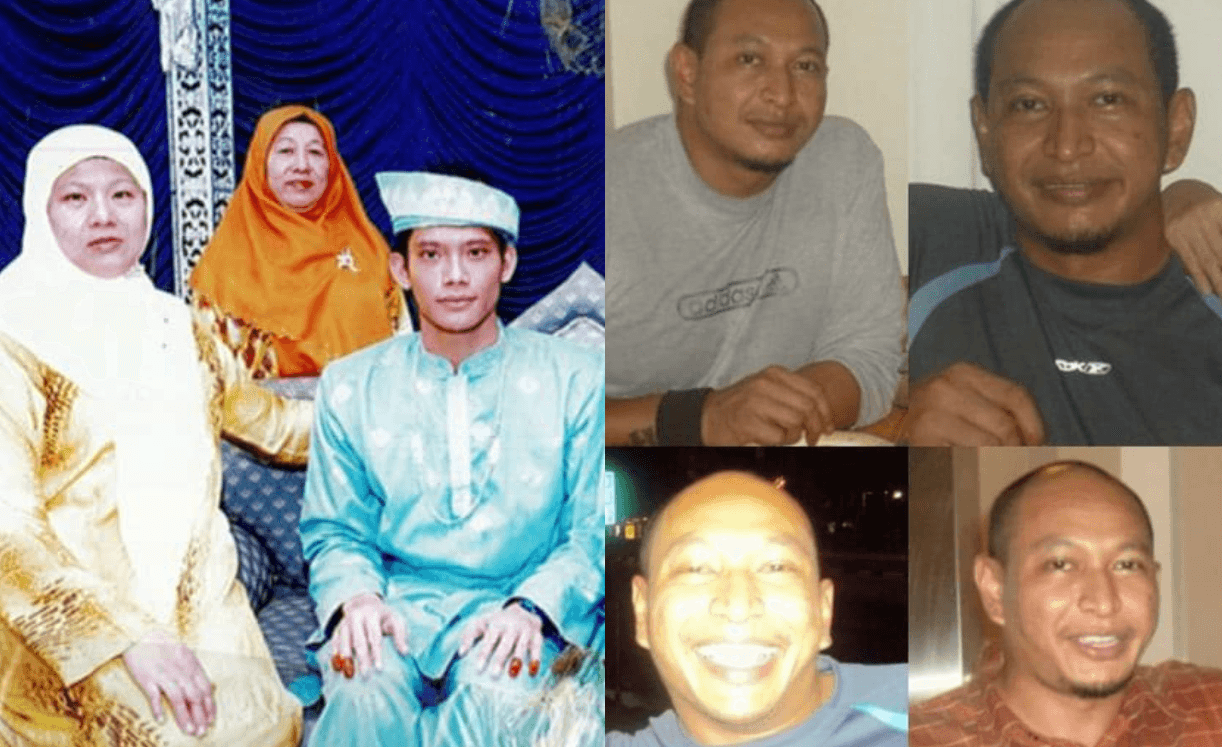

“There are currently 55 people on death row in Singapore, of which 30 are Singaporean Malays, 20 Indians, and five Chinese,” an activist in the city-state told MalaysiaNow.

It has also been learnt that of the 20 ethnic Indian convicts sentenced to death there, 15 are Malaysian.

As Singapore does not release statistics on death row prisoners, these numbers are painstakingly collated by activists and lawyers.

Malays make up about 13% of the republic’s population while Indians comprise 7%.

In a recent case, global rights group Amnesty International condemned the imminent execution of Syed Suhail Syed Zin, who was convicted in 2016 of possessing 38.84g of heroin.

A Singapore think tank has described the death sentence on Syed Suhail as “a grim reminder that Singapore’s factory of death has never ceased”.

Under Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act, anyone caught carrying more than 15g of the drug is sentenced to death.

Syed Suhail’s family members, who live in Malaysia, were informed just a week before his execution date on Sept 14 and told to make funeral arrangements – Singapore’s normal procedure for announcing the final days of those on death row.

“No allowance was made for them to travel from Malaysia before the execution of the sentence, given the ongoing Covid-19 restrictions,” said Think Center, a rare but vocal critic of government policies.

It also described Syed Suhail’s death sentence as “a grim reminder that Singapore’s factory of death has never ceased”.

For now, Syed Suhail remains in prison as he managed to obtain a reprieve.

As the fight against the death sentence continues, much of the weight appears to have fallen on the shoulders of lawyer M Ravi, who is known for handling high profile cases concerning human rights issues.

Ravi, who represents Syed Suhail, is also counsel for another convict – Moad Fadzir Mustaffa, who is slated for execution on Sept 24.

He recently complained that prison authorities had been leaking private communications from death row prisoners to the Attorney-General’s Chambers, even as attempts to thwart their death sentences continued.

According to him, these included a private communication between Syed Suhail and his family.

His revelation attracted condemnation from rights group Amnesty International.

“It is alarming that private correspondence between Syed Suhail and his then-lawyer was shared with the Attorney-General’s Chambers without any judicial orders or supervision of the process.

“This goes against a fundamental aspect of the right to a fair trial, which guarantees the right of defendants to maintain communications with their legal representatives within the professional relationship as confidential,” it said.

The fate of Fadzir and Syed Suhail now rests with the country’s highest courts, where their appeal to stay the execution order will be heard.

But recent cases suggest that their attempts might end up as another exercise in futility.

In May this year, 37-year-old Malaysian Punithan Genasan learnt with horror through Zoom that he had been sentenced to death by hanging.

He was accused of having links with two couriers carrying 28.5g of heroin in 2011. His defence that he had no knowledge of them was rejected.

Malaysian authorities extradited him to Singapore in 2016.

“The death penalty is always abhorrent, but to deliver this sentence, the harshest a defendant can receive, through the impersonal remoteness of a Zoom video call, is utterly inhumane,” Human Rights Watch said on the manner in which Punithan was sentenced.

But even against such odds, Ravi is determined to continue fighting for Syed Suhail and Fadzir.

He is calling for an independent audit on how confidential information between prisoners and their lawyers was obtained by government prosecutors and used in court.

Not one to mince words, Ravi has openly called for a reform of what he describes as a flawed system.

“There must be a full audit on this matter before lives are deprived of, and a moratorium on the death penalty should be put in place immediately. The law minister must act before it’s too late.

“We can rectify the situation because Syed is still alive. No judicial or legal system is foolproof, hence the death penalty is unsafe because death is irreversible and humans are fallible and so are systems,” the lawyer wrote in a post yesterday.

But beyond the rigid application of its mandatory death sentence, the Singapore government will also have to address concerns about the ethnic composition of those on death row, especially given its pride in the successful integration of its various communities.

The integration policy, among others, ensures a fair composition of ethnic groups in various sectors, extending to the point of preventing “racial enclaves” and ensuring an even mix throughout the country.

Since 1989, the Housing and Development Board has set a quota on who can reside in a public housing flat in a particular block or neighbourhood.

While such a policy may not be implemented in the justice system, the disparity in the racial composition of its death row prisoners may eventually necessitate a closer look.

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.