Inflation latest tough dish for US hospitality industry

While inflation is a drag on all companies, hospitality has many small businesses with fewer means to offset losses on one product with profits from another good.

Just In

New York restaurateur James Mallios has long prided himself on culinary authenticity, spending more for sunflower oil because it is used in Greece to fry foods.

But prices of the product more than tripled after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sidelined a major sunflower oil exporter, requiring a pivot to canola oil if Mallios’s small restaurant and catering business was going to survive.

Canola oil isn’t the same at all, but “there are bigger problems in the world,” Mallios says with a shrug.

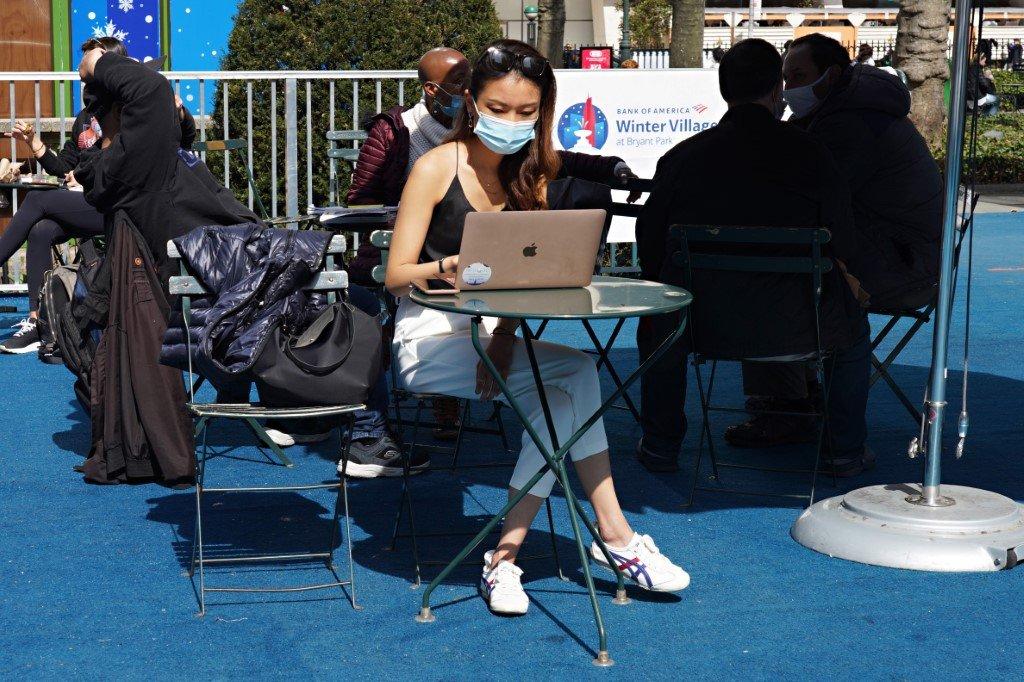

More than two years into Covid-19, hospitality companies are no longer shocked by the pandemic’s upheaval and the shape-shifting nature of the chaos.

They have been through the lockdown phase and its relaxation; the optimism of the post-vaccine period and the subsequent Omicron surge that reduced consumers and dashed hopes the pandemic was over; and the ongoing debates over whether Covid has become “endemic” and what that could mean for business.

Now they are dealing with inflation, a vexing monster in a consumer-facing industry at a time when shoppers are frustrated by higher gasoline prices.

At Amali, Mallios’s Manhattan restaurant, canola oil is no bargain either, in part because of increased demand from other restaurateurs who are also substituting for sunflower oil. Prices of canola oil have roughly tripled to $65 a jug, a major drag for an essential ingredient that isn’t even the main course.

“When you talk about things like butter, salt, fat that goes into pretty much every dish and those prices are increasing two and three and four times,” Mallios says. “That’s really where we see the pain the most.”

Companies in the hospitality industry are trying to be creative as they ride out the inflation wave, hoping for relief but not really expecting it anytime soon.

“There’s absolutely no way to conquer this with price,” Mallios says. “The market will not bear raising the price of a hamburger by US$30.”

After decades of anemic inflation in a dynamic that baffled economists, consumer price pressures have returned with a vengeance over the last year, the result of factors that include supply chain backlogs, the Ukraine war, Covid-19 manufacturing halts and strong consumer demand.

The Federal Reserve is under pressure to aggressively respond later this week after last Friday’s ugly consumer price index report that showed an 8.6% rise compared with a year earlier.

Accepting lower profits

May’s grim price action included the largest 12-month increase in the food-at-home index since 1979 and the biggest monthly increase in dairy products since 2007. Cereals, meats and fruits all had significant increases.

While inflation is a drag on all companies, hospitality has many small businesses with fewer means to offset losses on one product with profits from another good.

Olivier Dessyn, who owns three bakeries in New York, has raised prices – but not by much, only five or 10 cents on a pain au chocolat.

“If you’re a bakery, you can’t raise prices that high for something like a croissant,” he said. “The market won’t allow it. Nobody will come.”

Surging butter prices have necessitated a pivot.

“You can’t skimp on quality with butter,” said Dessyn. “If you change the butter, you need to change the recipe.”

But a part of the solution is simply to accept lower profit margins for now and survive the latest problem, Dessyn said.

At Blush, a San Francisco wine bar, the price range has shifted since the pandemic from about US$10 to US$14 per glass to around US$12 to US$16.

“At first, it was because of Covid, now it’s definitely more inflation,” said manager Vincent Nicolas, whose biggest worry right now is the supply chain for products.

“European beers and wines, it’s very, very up and down,” he said. “Sometimes we have to change, stop doing one wine and switch to something else.”

Raising prices carefully

Amali’s Mallios, too, remains anxious about the supply chain.

He understands the dynamics behind a price surge like for sunflower oil, but suspects “gouging” with some other price increases and wonders whether the government could do more in response.

Mallios is looking at ways to lower costs, perhaps by shifting some of the delivery items in-house. He is also spending on marketing in an effort to boost overall revenues as a way to maintain profits.

But raising prices takes dexterity. Perhaps a US$13 Caesar Salad could be $14 instead? Or a glass of wine that was US$14 might be lifted to US$16?

Of his four restaurants, which include a spot in the tony Hamptons, Mallios is most worried about his newest entrant, Bar Marseille in Queens, where more consumers are feeling the pinch of higher prices.

“It’s a middle-class neighborhood,” he said. “There’s only so much you can charge for a hamburger. Period, end of story.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.