Did vaccine inequality lead to the Omicron variant?

The WHO sounded the alarm on vaccine inequality again in September when countries with plenty of resources began eyeing booster shots for vaccinated adults and others considered vaccines for children.

Just In

In October 2020, as scientists around the world raced to develop a vaccine to fight Covid-19, the leader of the World Health Organization warned against looming “vaccine nationalism”.

In a video address, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at the time that the only way to beat the pandemic was by making sure poorer countries had fair access to a vaccine.

“When we have an effective vaccine, we must also use it effectively,” he said.

“And the best way to do that is to vaccinate some people in all countries rather than all people in some countries. Vaccine nationalism will prolong the pandemic, not shorten it.”

Over a year later, vaccine inequality is undeniable.

Rich nations like France and Japan have given at least one dose to over 75% of their populations.

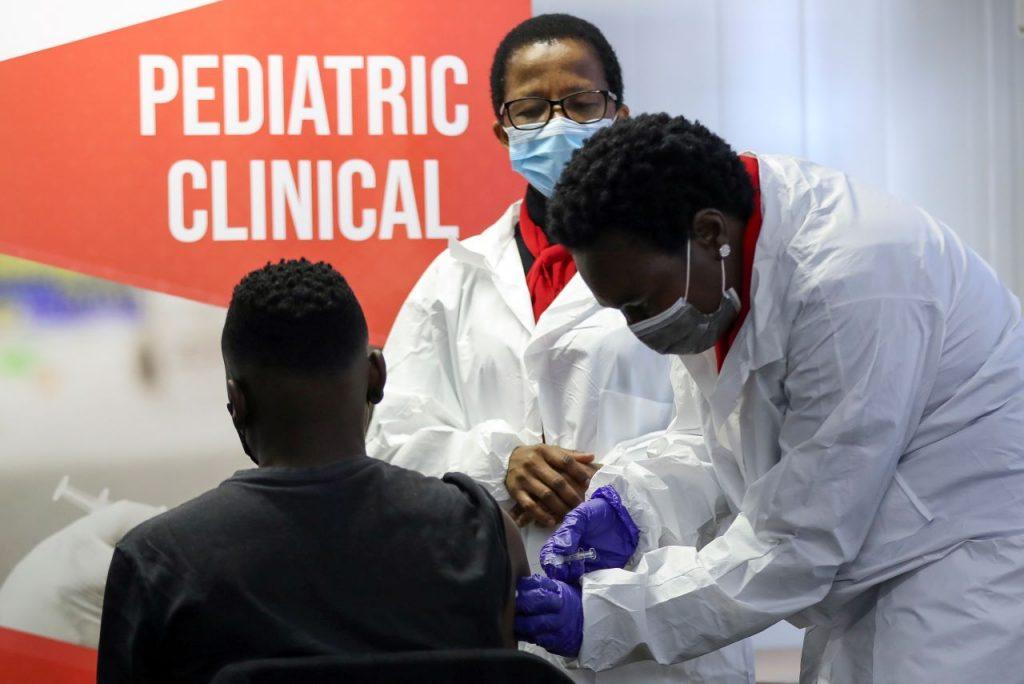

In South Africa – where the Omicron variant was first sequenced – only a quarter of the population has been vaccinated. This is one of the highest inoculation rates on the continent.

But is vaccine inequality the reason behind Omicron’s emergence?

French experts tasked with informing their government’s pandemic response say Omicron likely came from a patient with a depressed immune system and is the result of a long line of mutations that accumulated during a chronic infection.

But wherever it came from, its spread would have been “slower, the higher the immunity of the surrounding population,” Arnaud Fontanet, scientific advisory board member and epidemiologist at the Pasteur Institute, told AFP.

“You can imagine that the growth of the virus during uncontrolled epidemics creates more opportunities for variants to emerge,” he said.

‘Shock the world’

“I would like for this new worry to shock the world into realising the importance of vaccinating people on a global scale,” Fontanet said.

“The planet will only be safe when we achieve a level of global immunity that significantly limits the spread and opportunities for new variants to emerge,” he said.

The WHO sounded the alarm on vaccine inequality again in September when countries with plenty of resources began eyeing booster shots for vaccinated adults and others considered vaccines for children.

Speaking from WHO’s headquarters in Geneva, Tedros called on countries to avoid giving out extra Covid jabs until the end of the year, pointing to the millions worldwide who have yet to receive a single dose.

“I will not stay silent when the companies and countries that control the global supply of vaccines think the world’s poor should be satisfied with leftovers,” he said.

A global vaccine-sharing system called Covax, led by WHO and the Gavi vaccine alliance among others, is meant to provide 92 low- and middle-income countries with jabs financed by rich states.

Covax says it has succeeded in administering 500 million doses in 144 countries and territories, and on Monday, Chinese president Xi Jinping promised a billion vaccine doses to Africa through donations or subsidies for local production.

But in a joint statement on Monday, the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and Covax said the quality of donations needs to improve.

“The majority of the donations to-date have been ad hoc, provided with little notice and short shelf lives,” they said.

“This has made it extremely challenging for countries to plan vaccination campaigns and increase absorptive capacity.”

Fontanet agrees.

“Vaccinating the world is not only a question of doses,” he says.

“We have to support fragile health systems and work to persuade people to get the jabs.”

‘Follow the science’

Now that Omicron has been identified, countries are taking measures to prevent its spread by banning flights from Southern Africa where it seems to have originated.

Japan and Israel are closing their borders.

But epidemiologists say these sweeping gestures are beside the point.

“If you’re worried about your risk from omicron, get vaccinated if you aren’t already,” US virologist Angela Rasmussen tweeted on Sunday.

“Continue to layer other precautions. And more than anything, follow the science and advocate for collaborative global health. Travel bans won’t do [expletive]. Vaccines and global health equity WILL.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.