Foreigners increasingly reluctant to visit China as ‘spying’ arrests rise

Some fear that if a diplomatic spat between their government and Beijing occurs while they are visiting China they could become a target.

Academics, NGO workers and media professionals, who in pre-Covid times regularly travelled to China, now say they will be unwilling to do this once the pandemic restrictions are lifted, over fears for their personal safety and freedom.

Additionally, several in the international business community told CNN they would significantly modify their behaviour while outside China to avoid attracting the ire of authorities in the country, where they need to do business.

The dramatic detention of a handful of foreigners in recent years has instilled a deep fear in many old China hands, especially those with politically hazardous occupations.

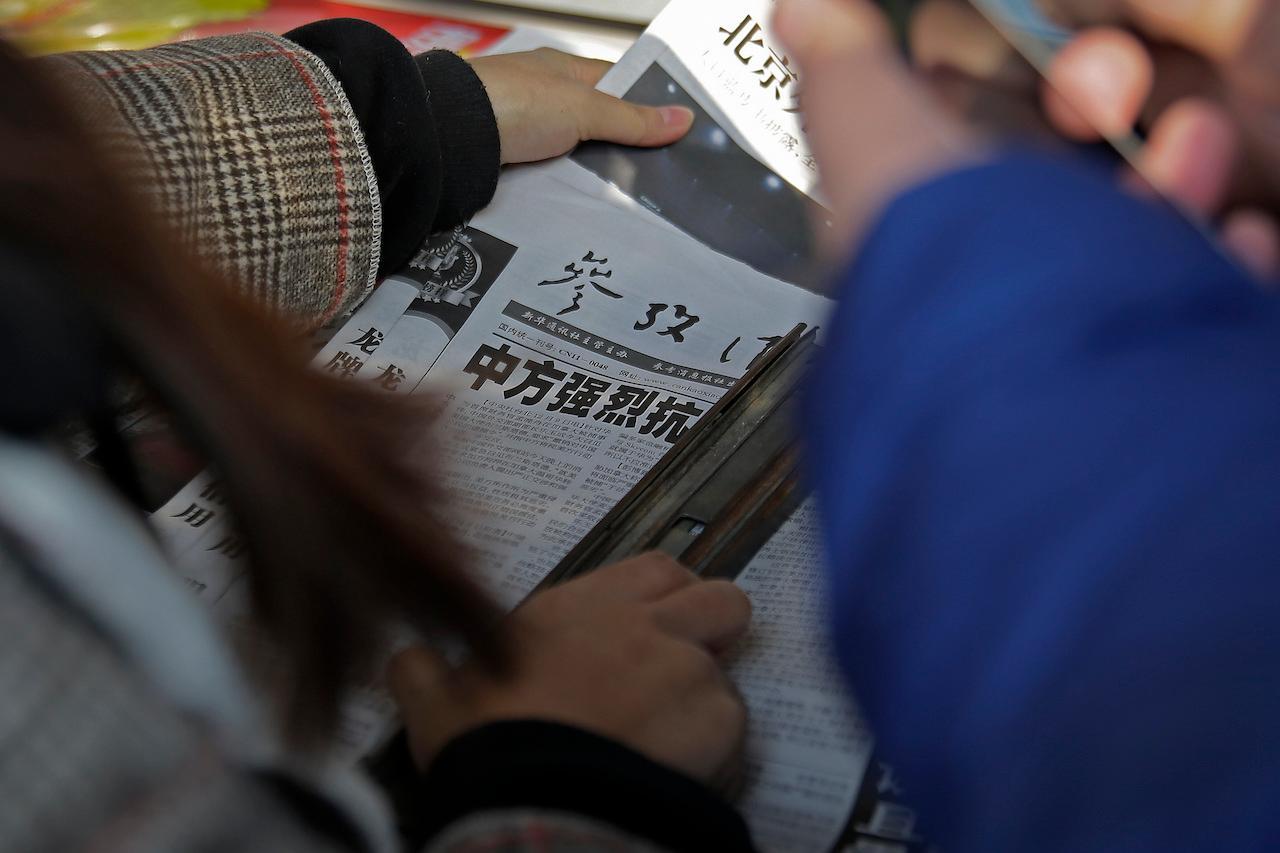

As President Xi Jinping breeds a culture of nationalism and forges increasingly hostile relations with Western governments, some fear that if a diplomatic spat between their government and Beijing erupts while they are visiting China they could become a target.

Many cited the detention of two Canadians in China in December 2018 as a turning point in their thinking.

An NGO worker and a travel organiser were detained just after Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou was arrested in Vancouver on charges filed in the US. Their detentions have been characterised as a bargaining chip to help leverage Meng’s release, an accusation Beijing denies.

Last August, Chinese-Australian TV anchor Cheng Lei was also detained amid worsening ties between Beijing and Canberra. Cheng’s detention was all the more surprising given that she worked for the state media channel, CGTN.

All three face charges of spying which could result in lengthy prison terms.

Gordon Matthews, a professor living in Hong Kong, says some of his colleagues at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who have devoted their lives to China are pursuing new lines of academic inquiry to avoid visiting the mainland.

William Nee, an American who works for NGO China Human Rights Defenders, is now unwilling to travel to China, and says he knows many others, with “a lower risk profile” than the two detained Canadians, who have made the same judgment.

“It’s not really a question only of, ‘What are the things I have been doing that may contribute to my getting detained?’ It’s also a question of, ‘What is my nationality? What have the politicians from my country been saying?'” Nee told CNN.

“If they’re willing to arbitrarily detain a very moderate, thoughtful academic, or a think tank type of person, then it’s difficult to see how anyone can feel safe in China.”

The Chinese foreign affairs ministry claimed in a statement that the “so-called increased risk of arbitrary detention of foreigners in China” was “completely inconsistent with the facts”.

After describing China as one of the safest countries to visit, the ministry statement said that in fact, Meng’s experience in Canada was a “typical case of arbitrary detention, and we hope she can return to China as soon as possible”.

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.