Not just survival of the fittest for orangutans in Sarawak reserve

The park rangers are also taking extra precautions to keep the primates safe from Covid-19.

Just In

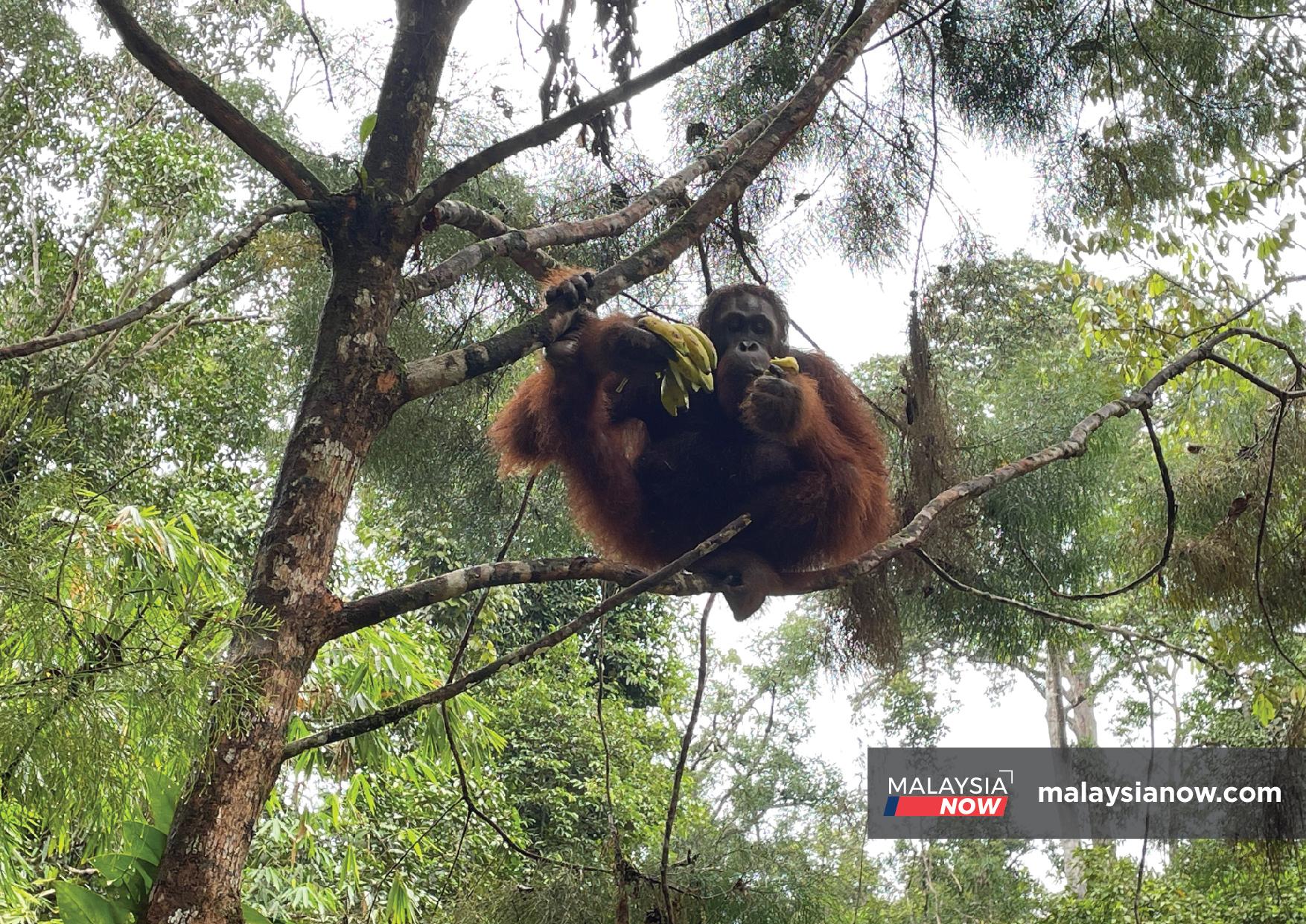

When breakfast is served in the morning, Anuar usually goes for the bananas first. After that, he zooms in on the coconuts, breaking them open and digging eagerly into the juicy meat inside.

Anuar is one of 25 semi-wild orangutans living at the Semenggoh Wildlife Reserve in Sarawak. Now 23, he was rehabilitated at the centre when he was a baby and learned his survival skills from the park rangers.

While he normally turns up for feeding sessions, he also knows how to forage for his own food, rumbling as he goes in a warning to other males to stay out of his way.

But he has a good relationship with the reserve staff, and can recognise those who habitually spend time with him, even when they are wearing face masks.

Ranger Murtadza Othman is one of them. Every day, he starts the morning by feeding the hungry apes. He goes out in search of them, calling each by name.

The orangutans get two meals a day, one in the morning and the other in the late afternoon. Such sessions once thrilled crowds of tourists who would flock to the reserve to visit the great apes.

But as with most other ecotourism businesses, the reserve has suffered greatly from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. While it once attracted 70,000 visitors each year, now only the wildlife rangers are left walking its paths.

Together with the other reserve personnel, Murtadza and fellow ranger Asraff Julaihi Khan do their best to protect their wards from the more immediate effects of the virus, especially infection.

“Even before the pandemic, visitors were not allowed to feed or take photos with the orangutans,” Asraff told MalaysiaNow.

“They must keep their distance to avoid the possibility of transmission as we don’t conduct Covid-19 tests on the orangutans here because we treat them as wildlife.”

Other safety measures like the wearing of face masks and gloves have also been put in place.

This is necessary as humans are capable of spreading the virus to other species.

Zoologist Dr Faisal Ali Anwarali Khan from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak pointed to an incident in which a number of gorillas living in captivity had tested positive for Covid-19.

“This has made people realise the importance of animal safety, for example the need to keep their distance from them,” Faisal told MalaysiaNow.

“If zoos do not normalise this measure, it will put us at higher risk of infection.”

‘They know us’

But the preventive measures do not appear to have alienated the orangutans from the rangers despite the extra efforts to keep the virus at bay.

“The orangutans know us and recognise us, even when they first saw us wearing face masks,” Asraff said.

“Last year during the lockdown, they spent more time in the forest. But there were also several times when they came over, just to greet us.”

The tree-top dwelling mammals are one of several dozen jungle species whose numbers have plummeted over the years, to the point that the Bornean orangutan is considered critically endangered.

It is difficult to estimate how many are left in the wild. A recent study said the number of orangutans remaining in Borneo was less than 100,000 in 2015, and predicted that another 45,000 would disappear within the next 30 years.

With such dangers in mind, the rangers are constantly on high alert to ensure the safety of those on the reserve. Every month, they venture into the forest, spending entire nights there to ward off poachers. Sometimes, they also use drones to help them patrol the area.

“We are also planning to instal camera trap technology in the forest,” Asraff said.

“This is a must because we have to submit a report on whether poachers are trying to enter our land. This forest is a protected area. No one is allowed to enter without a permit.”

In this regard, the Covid-19 lockdowns have proven a blessing in disguise, allowing them to spend more time in the forest in the absence of tourists and visitors.

They have also seen a significant increase in donations and volunteer efforts since the start of the pandemic.

“We receive a lot of requests to volunteer,” Asraff said. “People are also actively participating in our adoption programme for the orangutans.”

This, along with the growth in funds, means the reserve can afford to continue running throughout the pandemic.

Yet dangers still abound, most of them posed by human activity.

At the villages near the Semenggoh forest, clearing works are underway with lorries moving to and fro carrying loads of cement. Google Earth satellite images show that a small pocket of trees near the reserve has already disappeared.

A villager from Kampung Paya Mubit said the land in the area had been earmarked for housing developments.

Back at the reserve, the orangutans are safe – for now. Under the vigilant watch of the rangers, they continue their routine of playing, sleeping and eating, blissfully unaware of the threats that continue to linger just outside their doorstep.

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.